Planning for a distributed design system

Canonical

Design systems

Translating the Design System’s Vision into Action: A Professional Set of Tools, Rituals, and Practices

In November 2023, after six months of new management, I was entrusted with leading a Working Group dedicated to relaunching our design system. Initially, the group consisted of four designers, each dedicating 20% of their time to modernising our tooling and productising the system under a new mandate.

Since then, the team has grown to include 6 UX designers, 1 content designer, and 4 visual designers. In this case study, I will explain how I organised and led this team, establishing a professional framework to deliver on our vision.

At Canonical, our teams work fully remote and in different countries, but with significant overlap in time zones.

The starting point

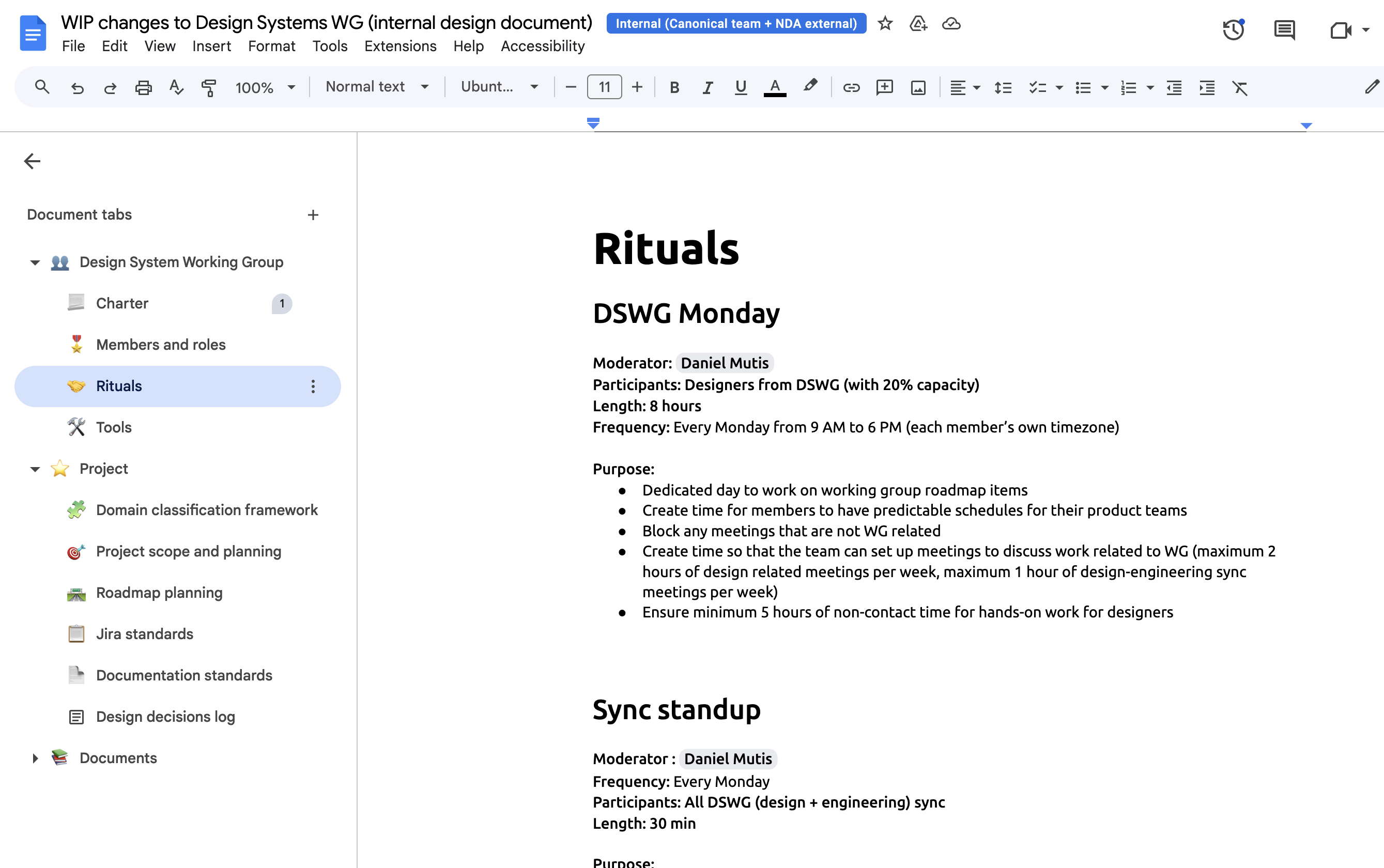

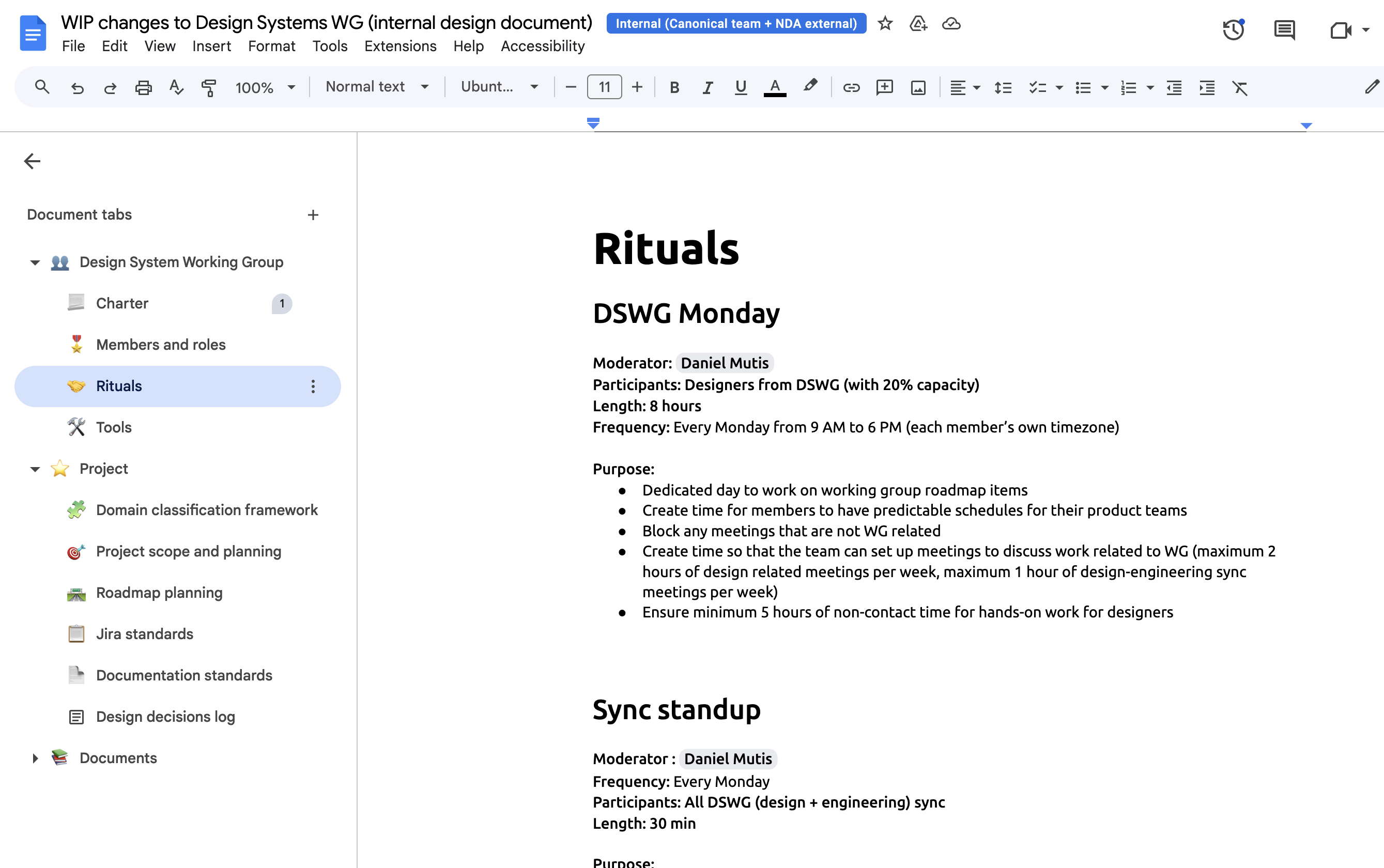

During the first six months, I focused on making the best use of the allocated time. I asked our designers to block a full day each week, free from any meetings related to other work. We found that Mondays worked best, as they tended to have fewer meetings and wouldn't disrupt their product work flow. This approach also encouraged higher engagement and fostered a social environment around the work, similar to a hackathon. It made the experience more enjoyable and created an element of accountability.

The initial challenges were mostly structural, so I scheduled working meetings where the team could discuss key decisions like the tiered system, the contributions process, and documentation workflows. As time passed and we refined our strategy, roles became more focused on individual interests and skills, allowing us to accomplish more work simultaneously. However, this also required increased evaluation, steering, and oversight, which led to the need for common rules and practices to scope, track, and review each other’s work.

The team playbook

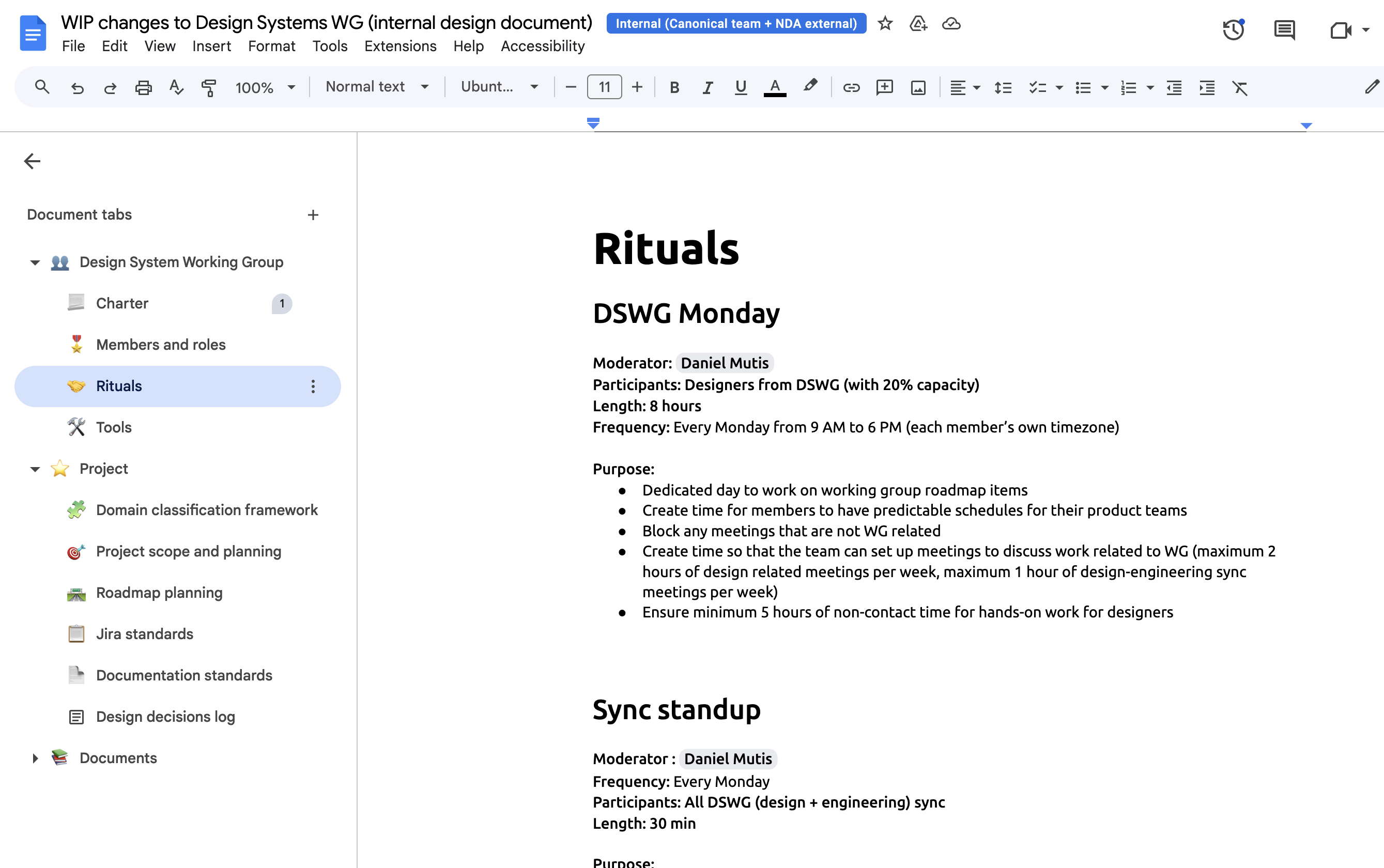

In conversations with managers and our engineering counterparts, we identified the need for a common source of truth about how our team operates and the standards for collaboration and work. This includes aspects such as work estimation and accurate time tracking, as well as unifying our meeting notes and providing a single document that anyone could reference to understand our goals and shared culture.

This playbook included some key pieces of information:

- General information about the group: a charter outlining the team’s purpose, a list of members and their roles, our recurring meetings, and all relevant links to resources like our Figma folder, code repository, and more.

- Project planning practices: our standards for tracking work in Jira, along with a domain classification framework to give structure to our sub-project names and provide a reliable way to understand the work being discussed at any given time.

- Other sources of truth: beyond team rules, we also needed to document solution specifications for stakeholder approval, which we compiled in a document called Brain; and a dedicated space for documenting work intended for our design system site, which we called “Design Systems Index”.

- Meeting notes: all non-project-specific meeting notes, such as standups and stakeholder updates, were documented in this section.

- A shared sources list: a collection of readings that have shaped our understanding of the project over time.

This document became the foundation of our ways of working and was later adopted and developed further by other working groups within the company.

Understanding the team

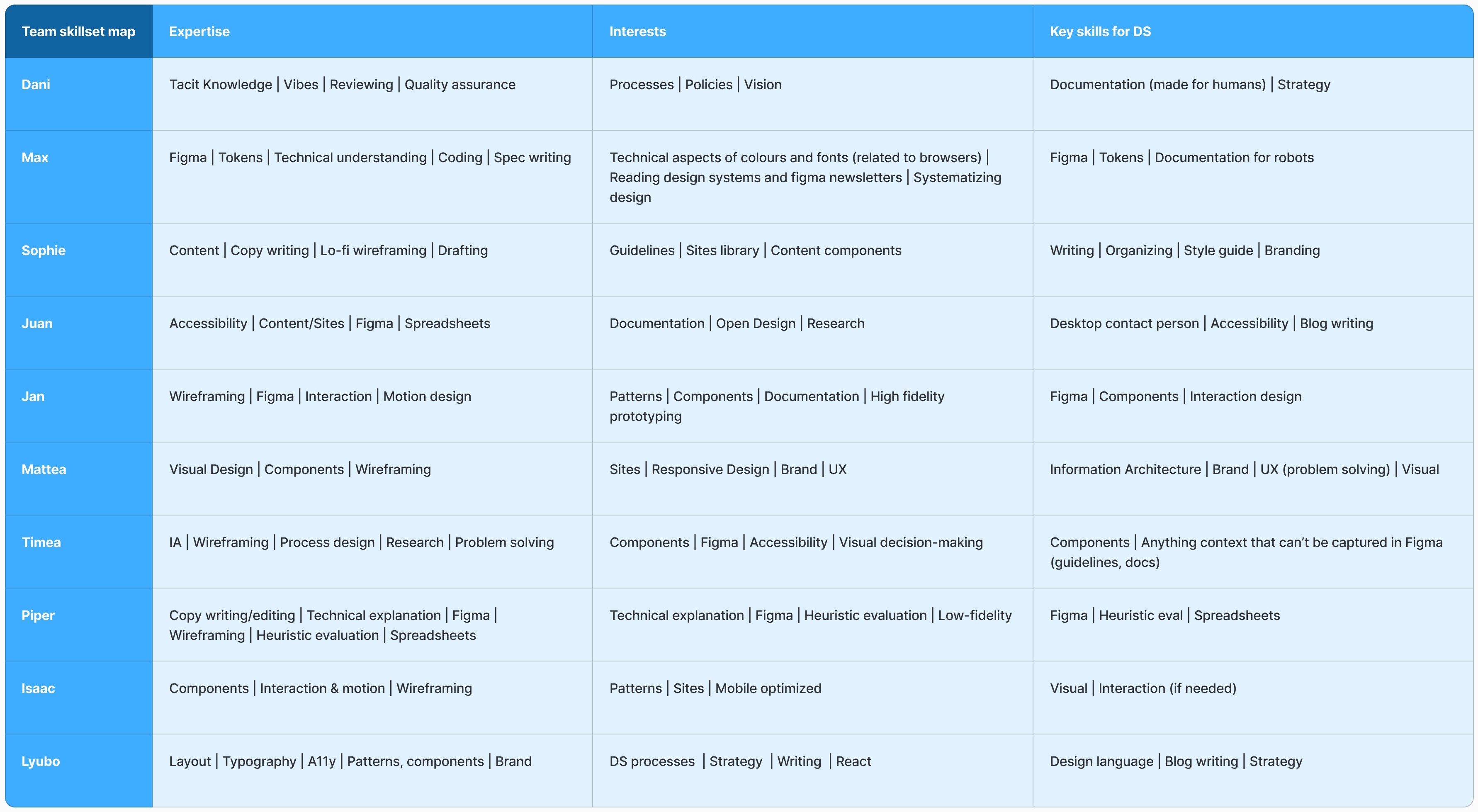

Our working group is an area that each team member voluntarily chooses to contribute to, offering an opportunity to work on horizontal initiatives for the design team, alongside their product team responsibilities. Given these circumstances, I aimed to make the work as enjoyable and rewarding as possible, within the boundaries of our vision and stakeholder expectations. I also saw this as a chance for team members to develop skills that would support their career progression — for example, helping a mid-level designer learn to autonomously generate work within an uncertain scope.

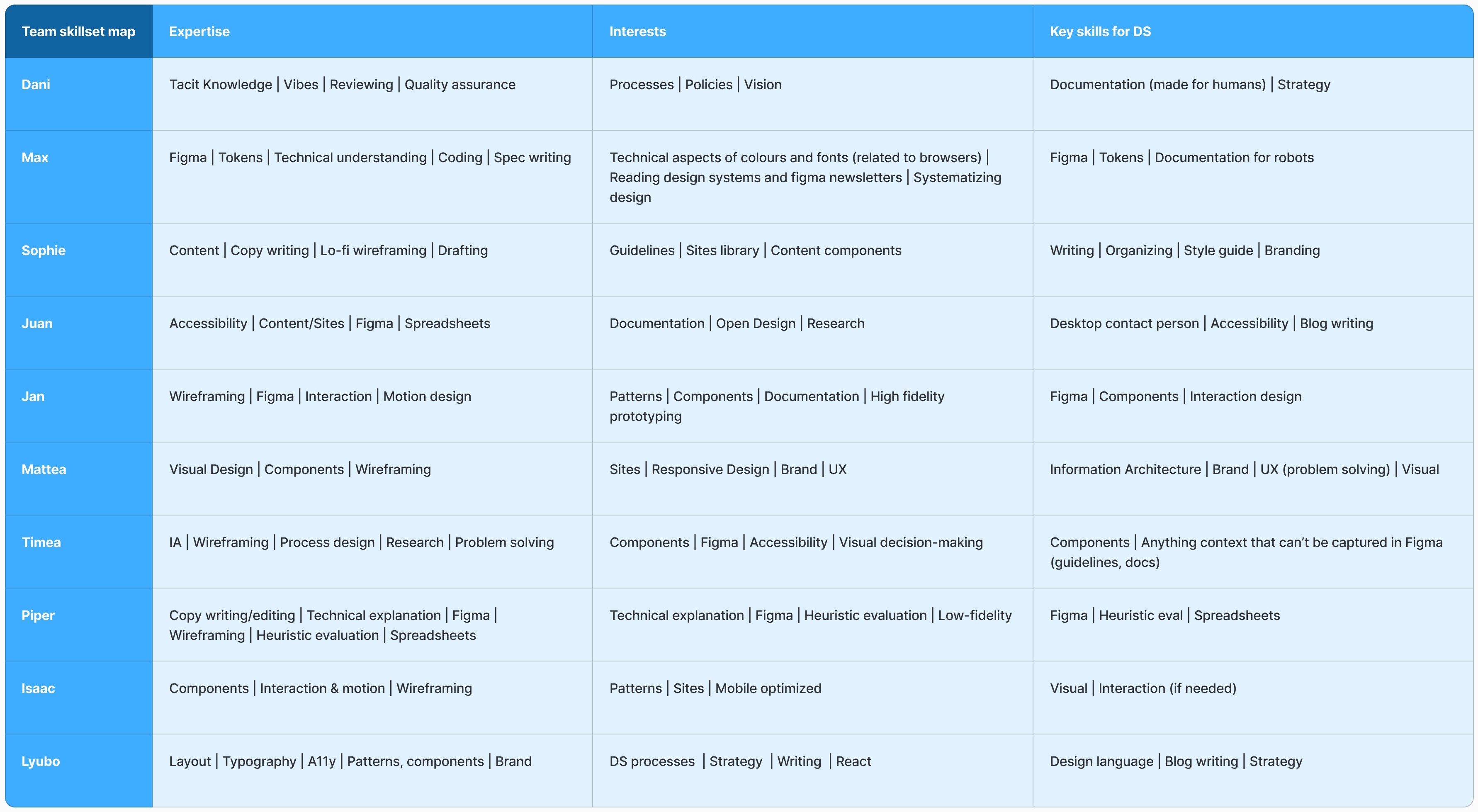

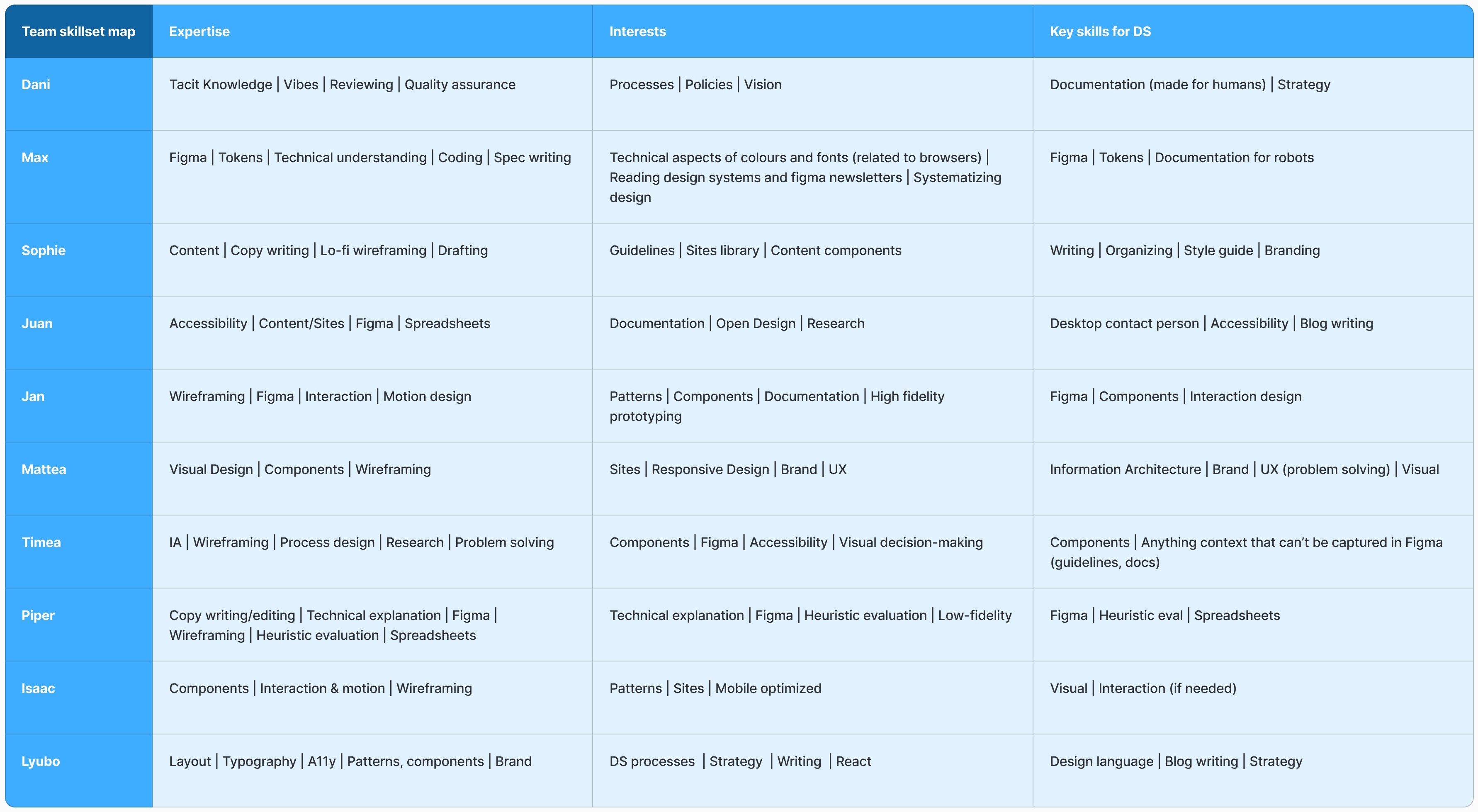

With these values in mind, I led a workshop to map the team’s skills, interests, and specific design system expertise, which later helped us allocate resources more intentionally across projects.

Mapping the project

To deepen our knowledge of design systems, we consistently referred to key thought leaders in the field, such as Nathan Curtis and Nate Baldwin from Adobe Spectrum. We also drew lessons from established systems like IBM’s Carbon, the GOV.UK Design System, Adobe Spectrum, GitHub’s Primer, among others.

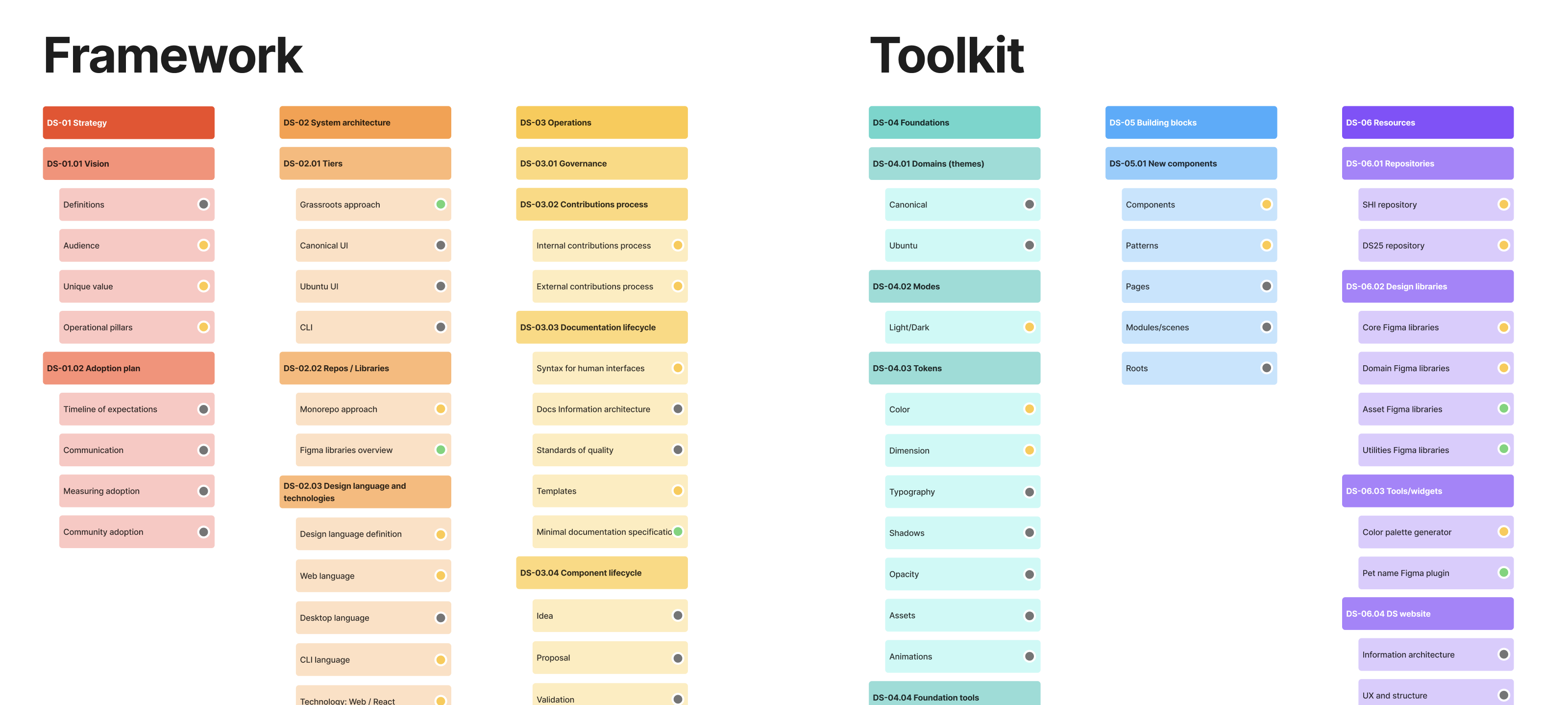

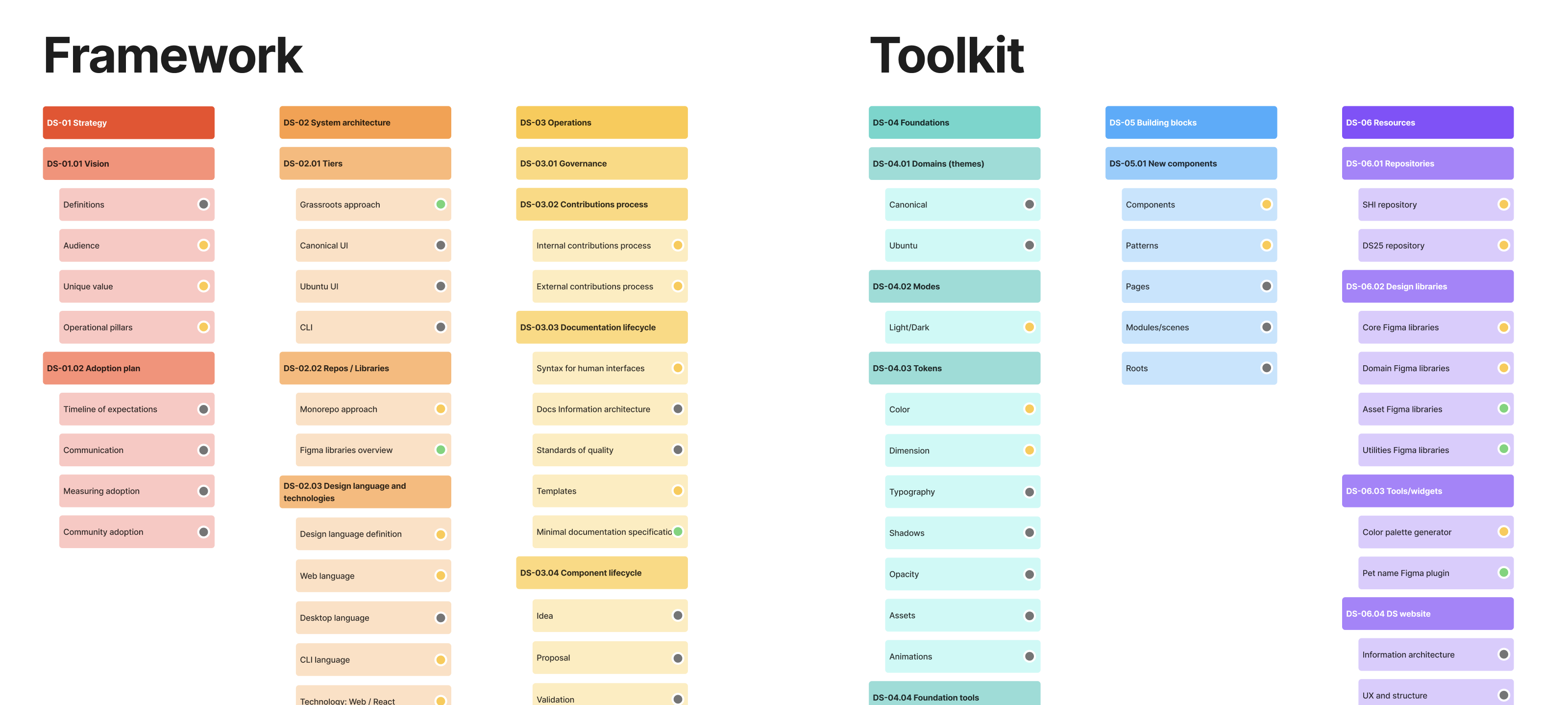

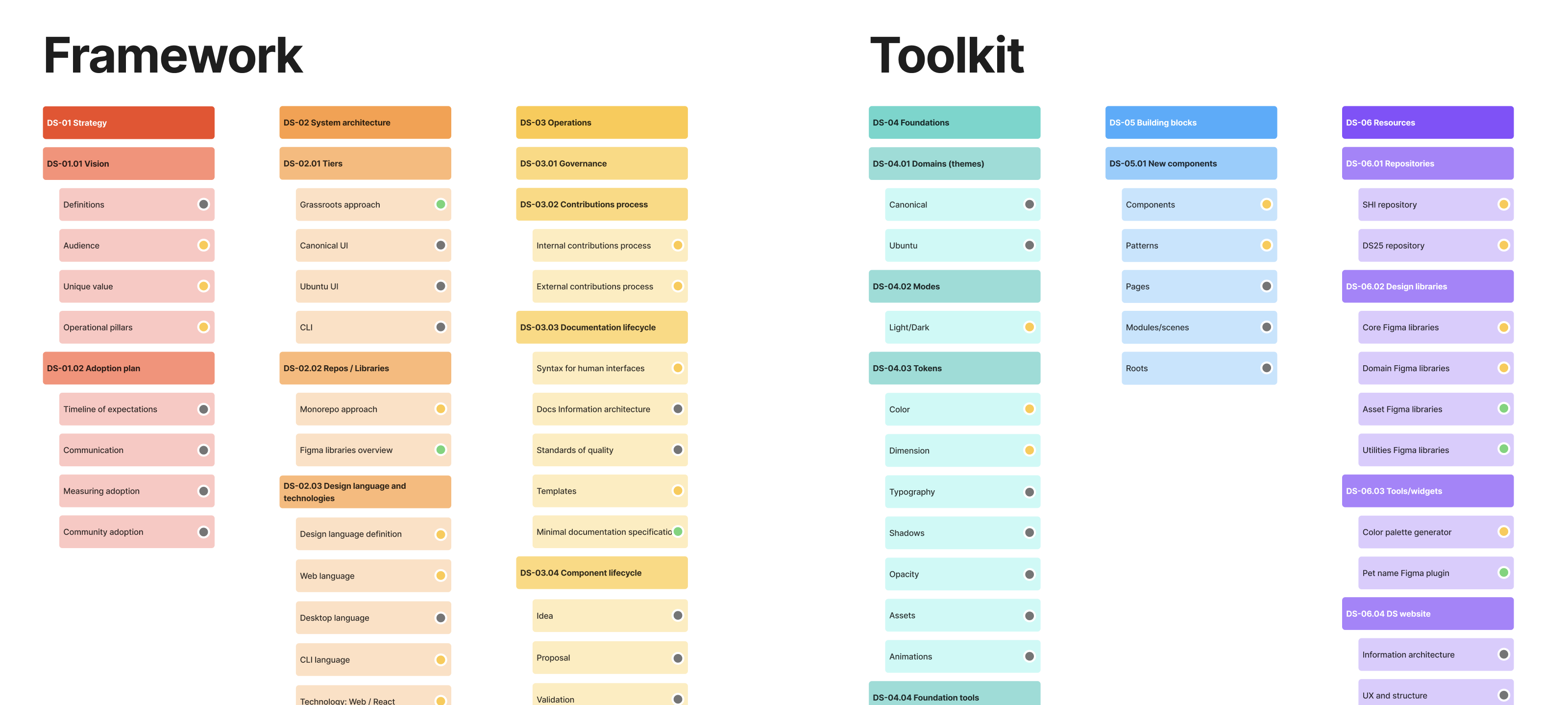

Based on this understanding, I mapped the project to capture every possible area of work needed to reach a good level of completion for the system. I divided the project into three main sections:

- Framework: this includes all the foundational work where we define our theoretical approach and make decisions on structure, processes, and tools. For example, this covers our approach to Figma libraries and key processes like the Contributions process.

- Toolkit: this section focuses on the main ways our users interact with the system. These are the resources that most designers and engineers will consume, and they represent the practical implementation of the Framework decisions. Examples include our libraries, code repositories, and documentation sites.

- BAU (business as usual): both the Framework and Toolkit categories involve recurring work, from the lifecycle management of different elements, to updates based on new data or insights, or general maintenance. This category groups all of that ongoing work.

Each area of the system is composed of pillars of work, which are the main categories we used to group tasks of a similar nature. These are:

Framework:

- Strategy: the vision and adoption plan.

- System architecture: structural decisions, such as tiers, component levels, library hierarchy, etc.

- Operations: processes like the documentation lifecycle or the contributions process.

Toolkit:

- Foundations: the translation of brand elements into tokens.

- Building blocks: essential elements like components, patterns, and modules that designers and developers use to build UIs.

- Resources: assets like the actual libraries and the documentation websites.

These pillars are made up of our projects, also known in Jira as Objectives, within which we organise all the pieces of work required to complete them, commonly known as Epics.

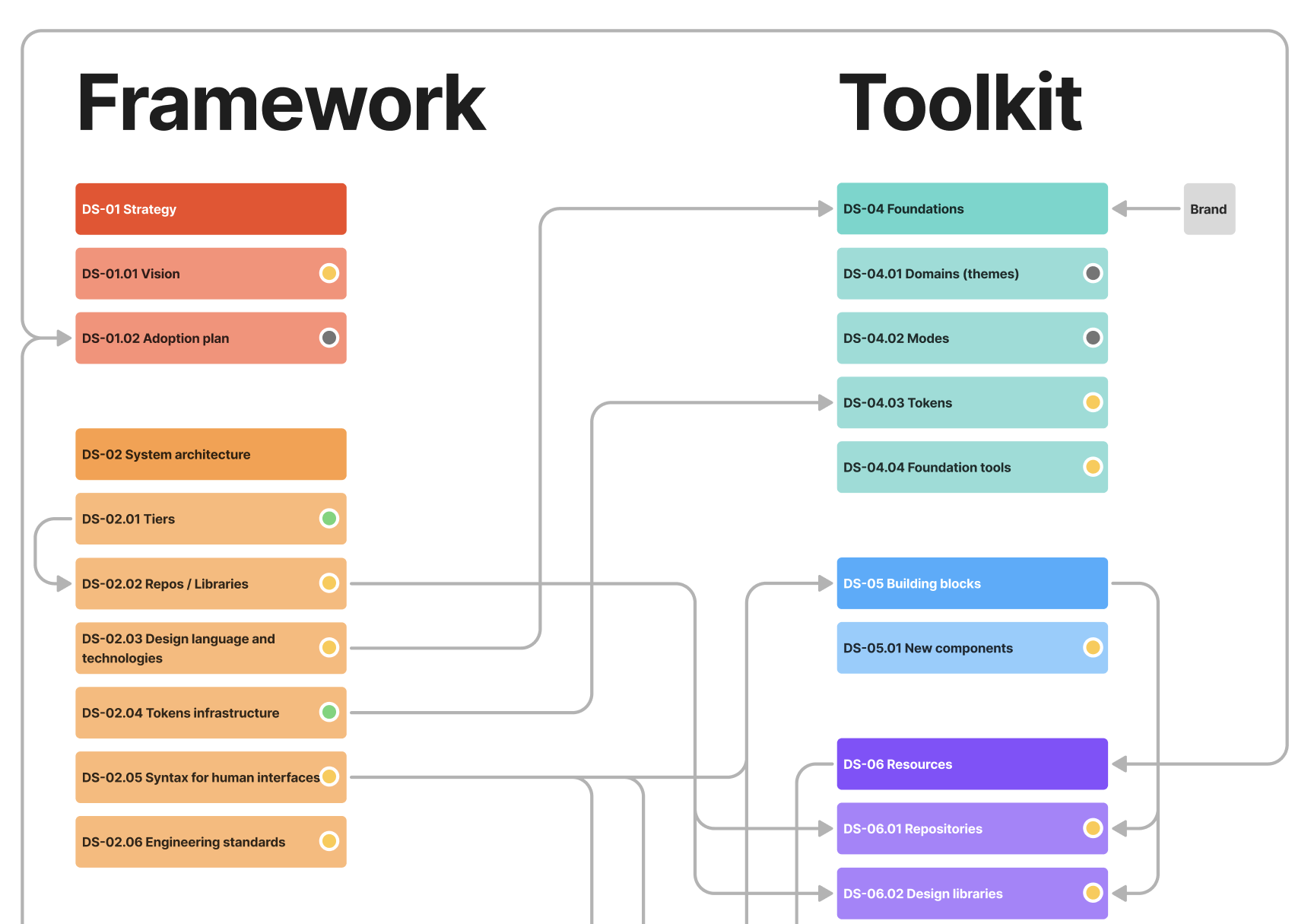

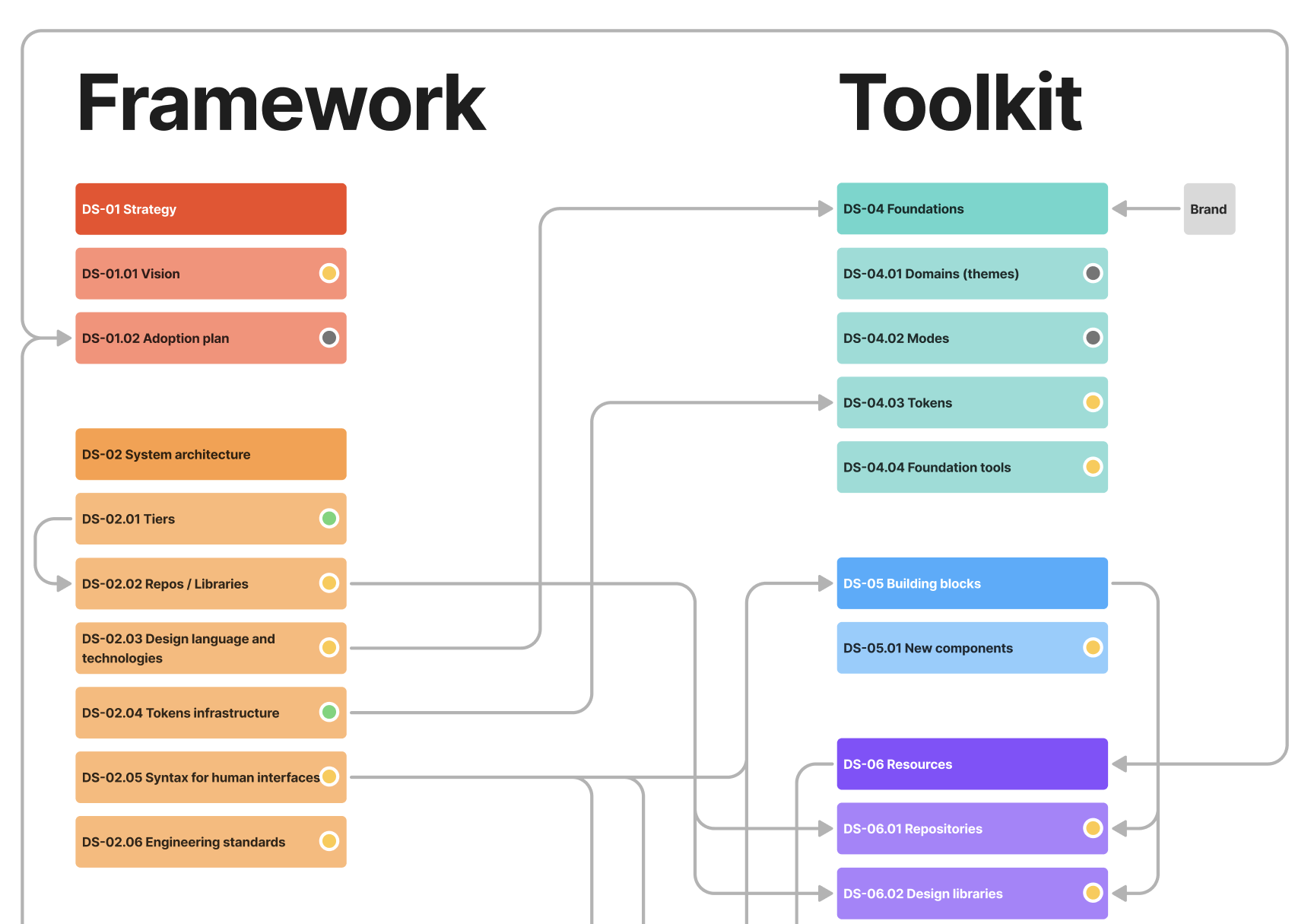

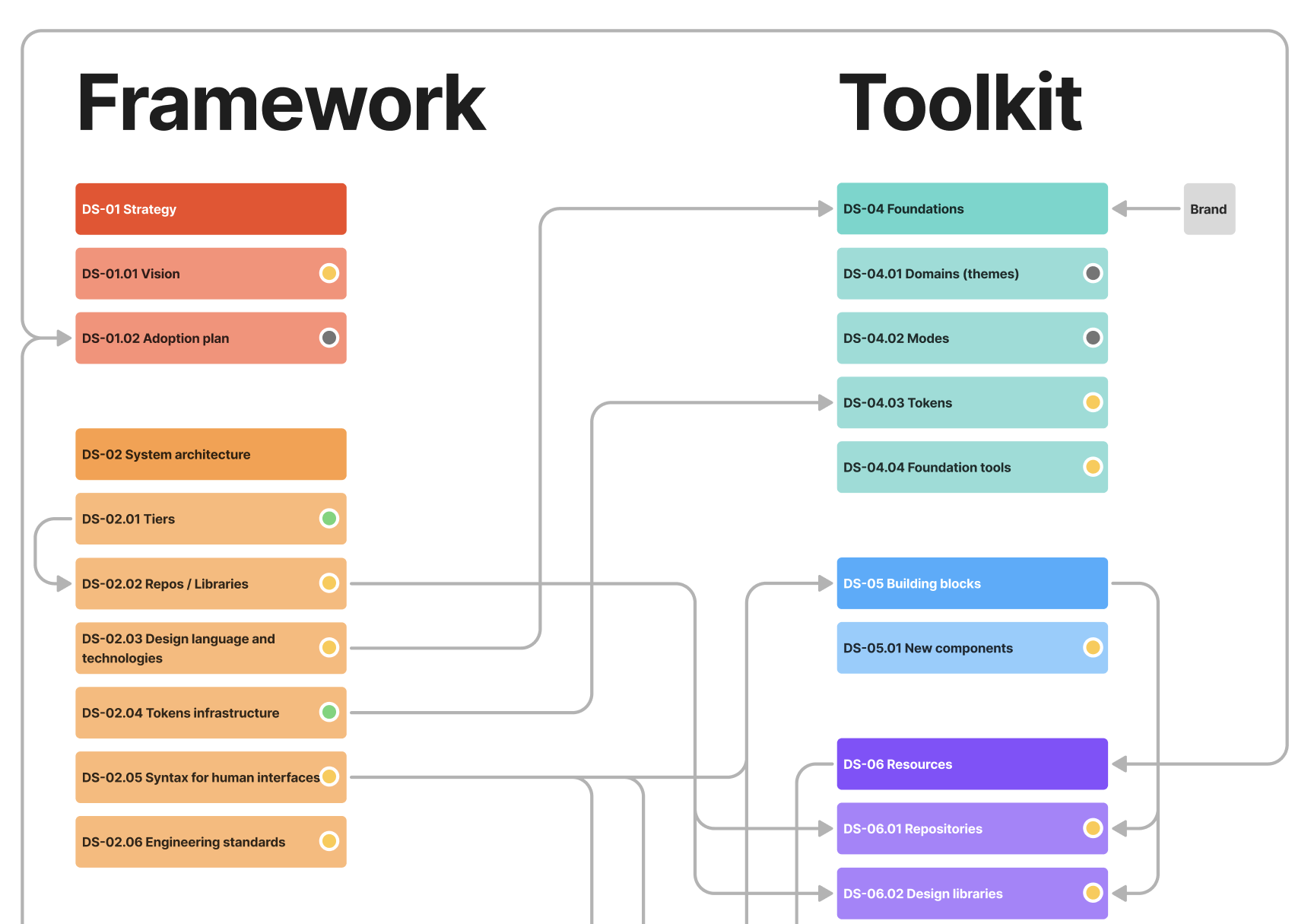

To further understand the sequencing of work in the project, I mapped all dependencies between different projects, which helped us identify what work was blocked by other tasks.

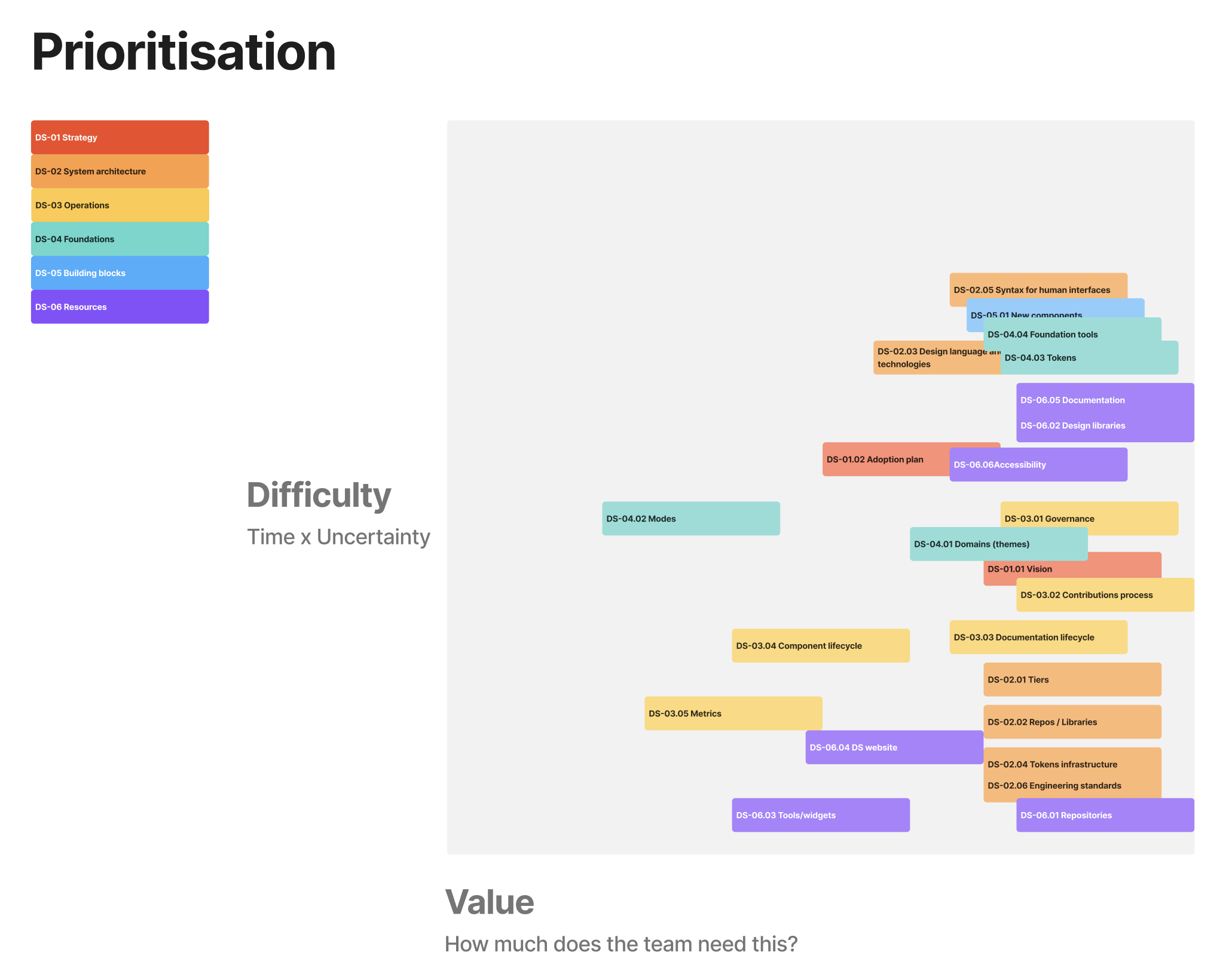

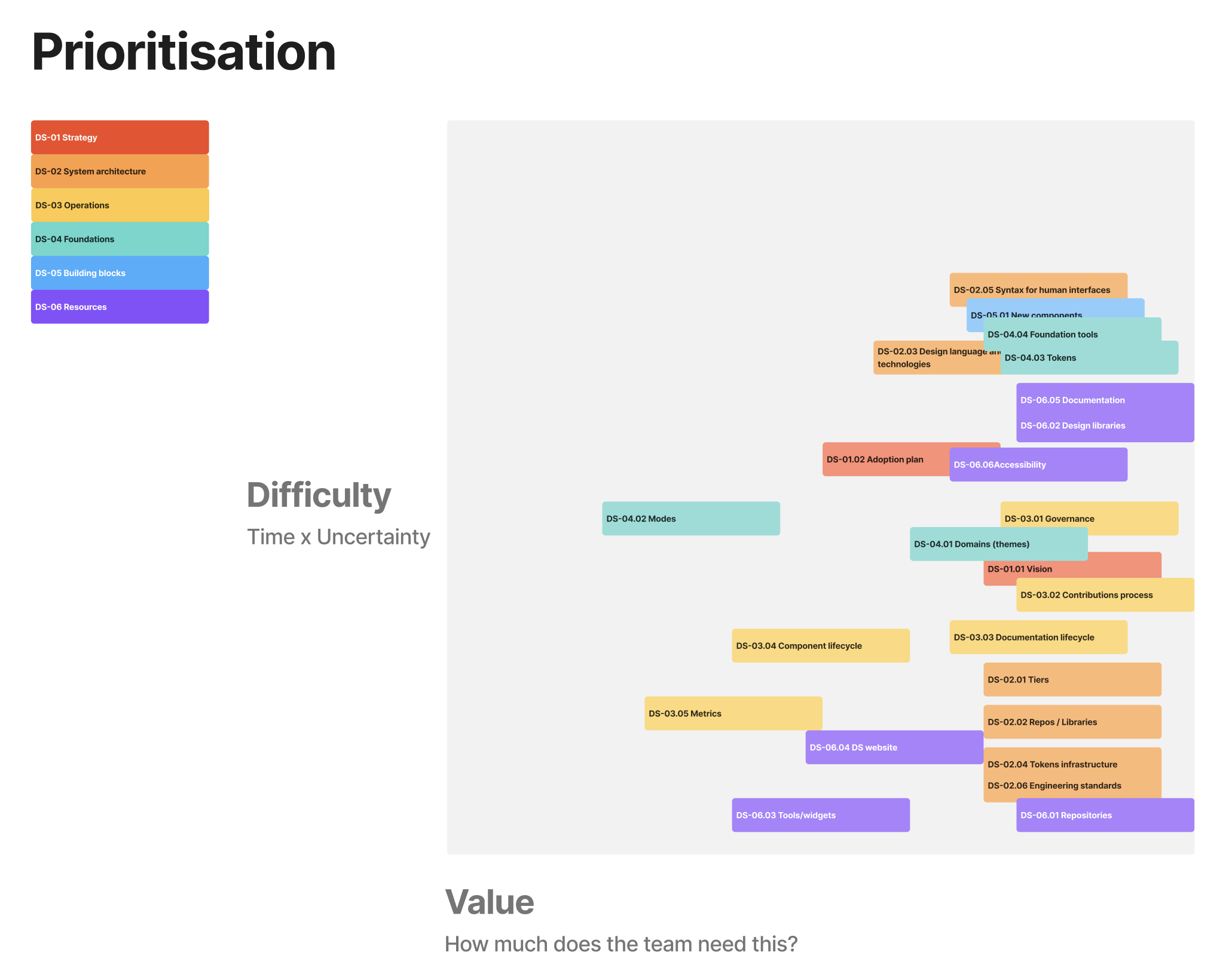

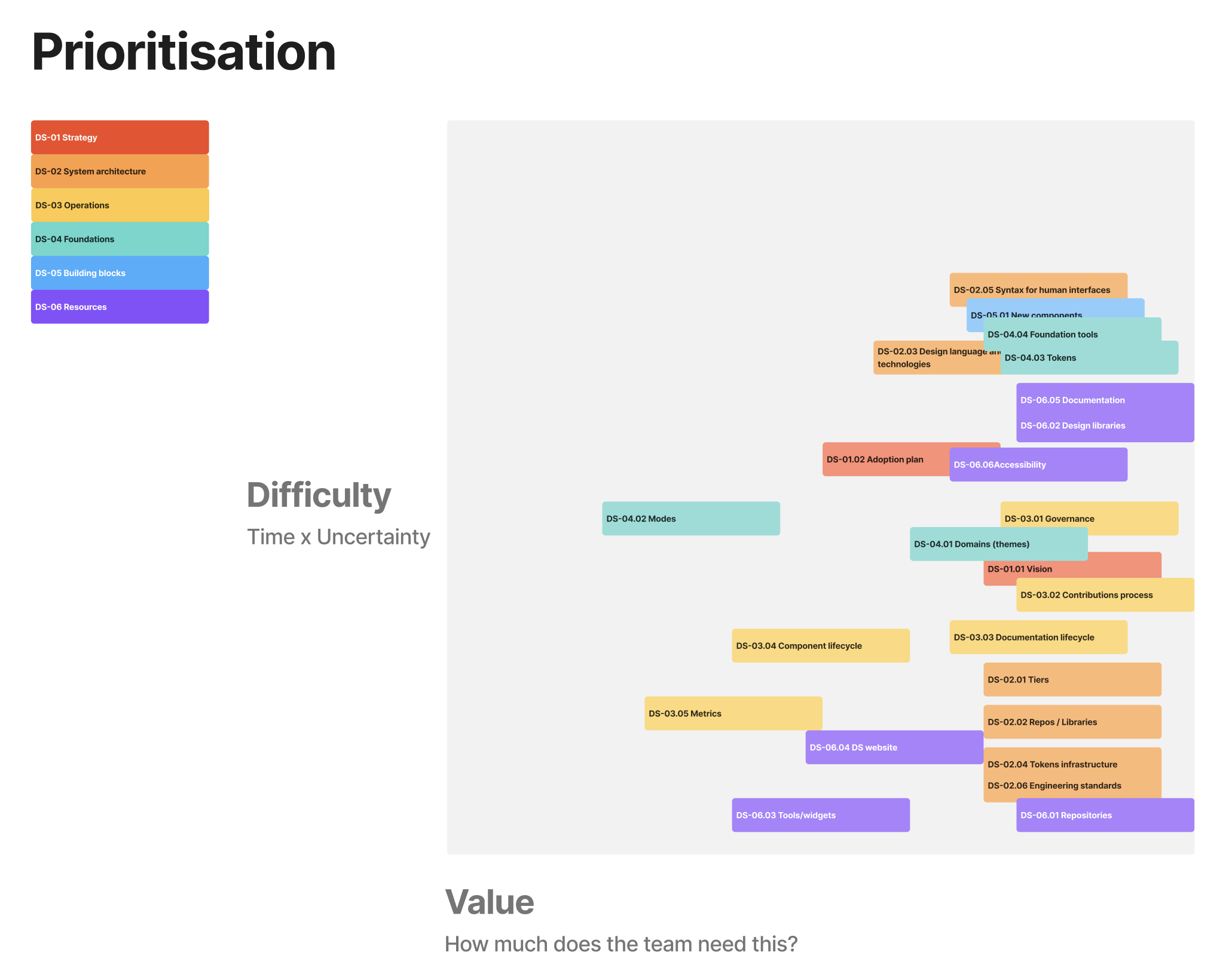

Finally, to provide a timeline of work to achieve an MVP of the new design system, I led a workshop with all key stakeholders (design management, engineering management, brand designer, and the project leads within the working group) to understand the priorities between different pieces of work. We mapped all projects across two axes:

- Effort: understood as the combination of the time the task would require and the amount of uncertainty linked to it.

- Value: the impact this piece of work would have once completed in helping the teams achieve their goals.

Domain classification system and Project plan

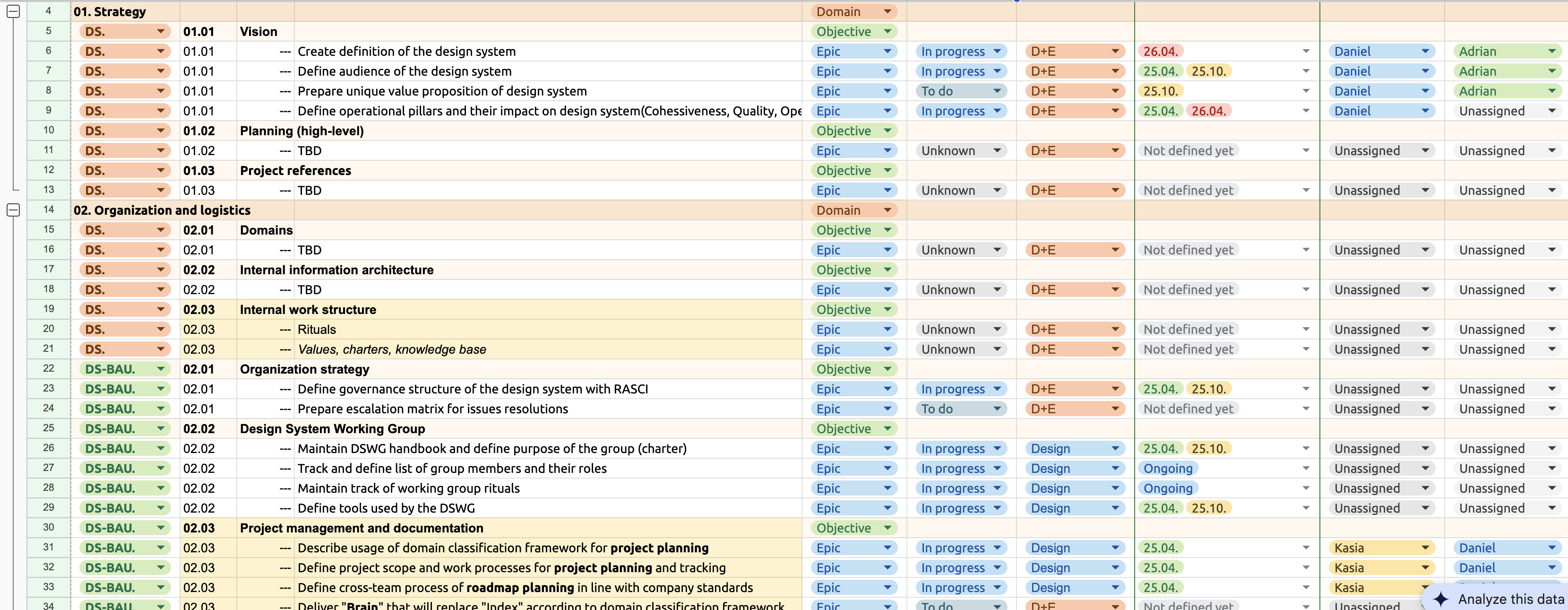

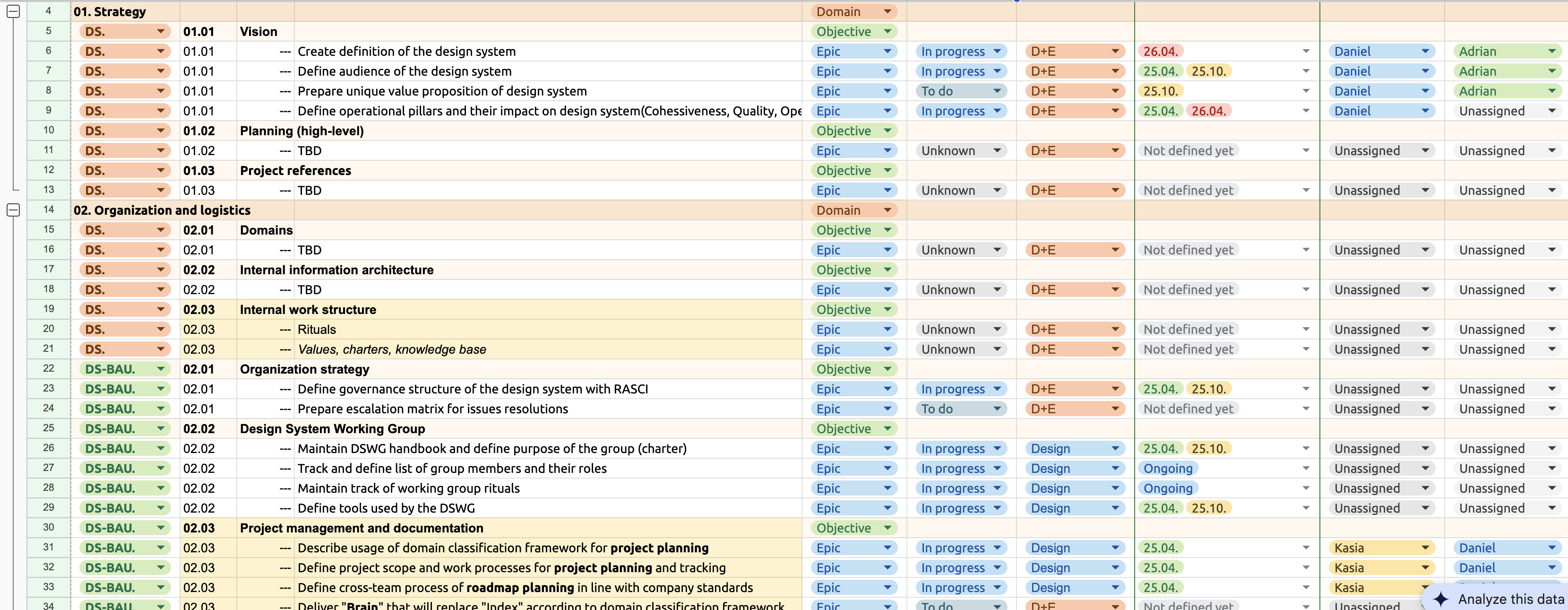

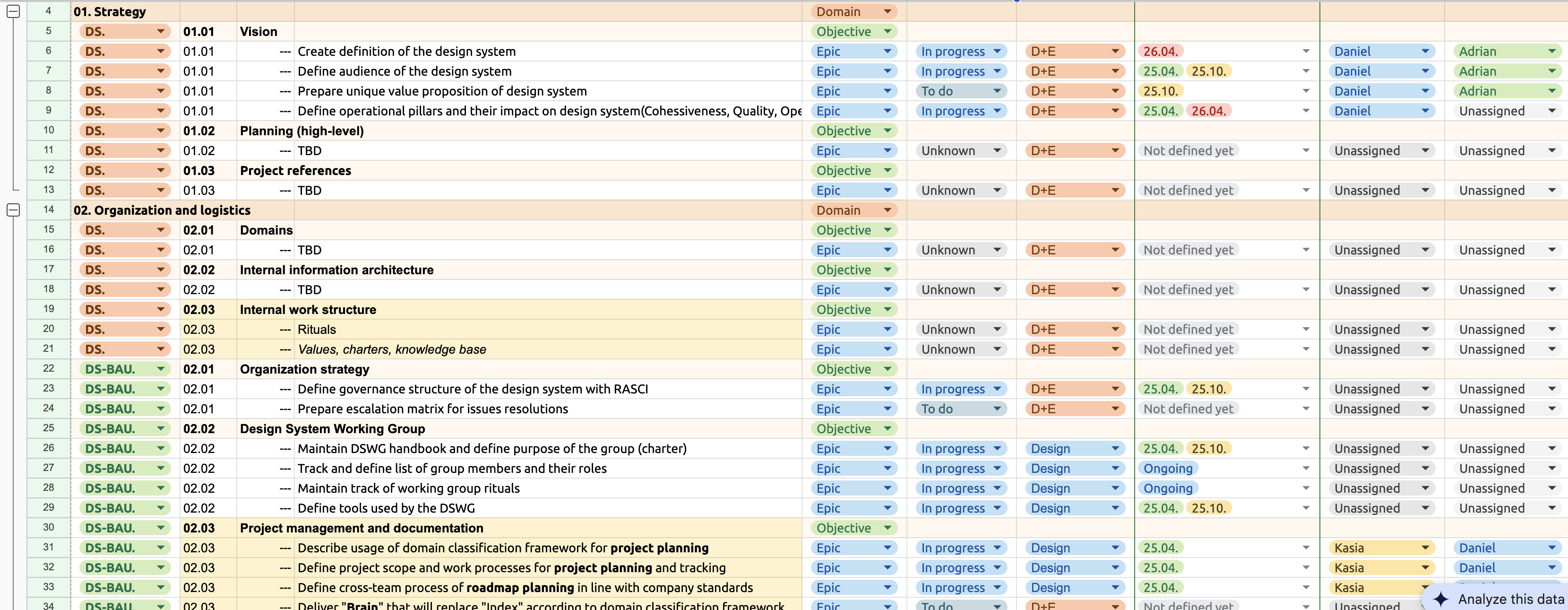

- In order to provide clear indicators of what work each document, task, or meeting is related to, we came up with a domain system that identifies each project with a unique combination of names and numbers. This system is divided into the following parts:

- Domain ID: a combination of letters and numbers, unique to each project.

- Domain name: the name of the pillar the piece of work belongs to.

- Domain area: the specific project inside the pillar.

For example, our contributions project was named:

DS-03.02 | Operations | Contributions process

These domains are then used in our Jira objectives and epics, as well as in every document related to that piece of work, giving us a common language to reference and identify each project.

The combination of this domain system and the project map formed our Project Plan, which we built using Google Sheets and connected to all relevant pieces of information. This plan became a very useful tool for phasing the work over time, planning roadmaps, and assigning responsibilities using a RASCI matrix.

All these tools helped us professionalise the team’s practices, enabling us to measure and track the work we produce — an invaluable asset when discussing project resourcing and demonstrating our impact. They also provide the team with certainty, establishing a shared rulebook that supports smooth collaboration and well-documented outcomes.

I made sure to communicate openly and to consider the team’s voices throughout the project, using methods like retrospectives to evaluate our satisfaction with the framework and identify areas for improvement.

One recurring challenge has been the difficulty of keeping systems like Jira up to date while also focusing on producing work. We plan to address this by establishing shared routines and guiding the team through maintaining these tools, with the goal of building confidence and a stronger sense of ownership.

Other design systems work

Planning for a distributed design system

Canonical

Design systems

Translating the Design System’s Vision into Action: A Professional Set of Tools, Rituals, and Practices

In November 2023, after six months of new management, I was entrusted with leading a Working Group dedicated to relaunching our design system. Initially, the group consisted of four designers, each dedicating 20% of their time to modernising our tooling and productising the system under a new mandate.

Since then, the team has grown to include 6 UX designers, 1 content designer, and 4 visual designers. In this case study, I will explain how I organised and led this team, establishing a professional framework to deliver on our vision.

At Canonical, our teams work fully remote and in different countries, but with significant overlap in time zones.

The starting point

During the first six months, I focused on making the best use of the allocated time. I asked our designers to block a full day each week, free from any meetings related to other work. We found that Mondays worked best, as they tended to have fewer meetings and wouldn't disrupt their product work flow. This approach also encouraged higher engagement and fostered a social environment around the work, similar to a hackathon. It made the experience more enjoyable and created an element of accountability.

The initial challenges were mostly structural, so I scheduled working meetings where the team could discuss key decisions like the tiered system, the contributions process, and documentation workflows. As time passed and we refined our strategy, roles became more focused on individual interests and skills, allowing us to accomplish more work simultaneously. However, this also required increased evaluation, steering, and oversight, which led to the need for common rules and practices to scope, track, and review each other’s work.

The team playbook

In conversations with managers and our engineering counterparts, we identified the need for a common source of truth about how our team operates and the standards for collaboration and work. This includes aspects such as work estimation and accurate time tracking, as well as unifying our meeting notes and providing a single document that anyone could reference to understand our goals and shared culture.

This playbook included some key pieces of information:

- General information about the group: a charter outlining the team’s purpose, a list of members and their roles, our recurring meetings, and all relevant links to resources like our Figma folder, code repository, and more.

- Project planning practices: our standards for tracking work in Jira, along with a domain classification framework to give structure to our sub-project names and provide a reliable way to understand the work being discussed at any given time.

- Other sources of truth: beyond team rules, we also needed to document solution specifications for stakeholder approval, which we compiled in a document called Brain; and a dedicated space for documenting work intended for our design system site, which we called “Design Systems Index”.

- Meeting notes: all non-project-specific meeting notes, such as standups and stakeholder updates, were documented in this section.

- A shared sources list: a collection of readings that have shaped our understanding of the project over time.

This document became the foundation of our ways of working and was later adopted and developed further by other working groups within the company.

Understanding the team

Our working group is an area that each team member voluntarily chooses to contribute to, offering an opportunity to work on horizontal initiatives for the design team, alongside their product team responsibilities. Given these circumstances, I aimed to make the work as enjoyable and rewarding as possible, within the boundaries of our vision and stakeholder expectations. I also saw this as a chance for team members to develop skills that would support their career progression — for example, helping a mid-level designer learn to autonomously generate work within an uncertain scope.

With these values in mind, I led a workshop to map the team’s skills, interests, and specific design system expertise, which later helped us allocate resources more intentionally across projects.

Mapping the project

To deepen our knowledge of design systems, we consistently referred to key thought leaders in the field, such as Nathan Curtis and Nate Baldwin from Adobe Spectrum. We also drew lessons from established systems like IBM’s Carbon, the GOV.UK Design System, Adobe Spectrum, GitHub’s Primer, among others.

Based on this understanding, I mapped the project to capture every possible area of work needed to reach a good level of completion for the system. I divided the project into three main sections:

- Framework: this includes all the foundational work where we define our theoretical approach and make decisions on structure, processes, and tools. For example, this covers our approach to Figma libraries and key processes like the Contributions process.

- Toolkit: this section focuses on the main ways our users interact with the system. These are the resources that most designers and engineers will consume, and they represent the practical implementation of the Framework decisions. Examples include our libraries, code repositories, and documentation sites.

- BAU (business as usual): both the Framework and Toolkit categories involve recurring work, from the lifecycle management of different elements, to updates based on new data or insights, or general maintenance. This category groups all of that ongoing work.

Each area of the system is composed of pillars of work, which are the main categories we used to group tasks of a similar nature. These are:

Framework:

- Strategy: the vision and adoption plan.

- System architecture: structural decisions, such as tiers, component levels, library hierarchy, etc.

- Operations: processes like the documentation lifecycle or the contributions process.

Toolkit:

- Foundations: the translation of brand elements into tokens.

- Building blocks: essential elements like components, patterns, and modules that designers and developers use to build UIs.

- Resources: assets like the actual libraries and the documentation websites.

These pillars are made up of our projects, also known in Jira as Objectives, within which we organise all the pieces of work required to complete them, commonly known as Epics.

To further understand the sequencing of work in the project, I mapped all dependencies between different projects, which helped us identify what work was blocked by other tasks.

Finally, to provide a timeline of work to achieve an MVP of the new design system, I led a workshop with all key stakeholders (design management, engineering management, brand designer, and the project leads within the working group) to understand the priorities between different pieces of work. We mapped all projects across two axes:

- Effort: understood as the combination of the time the task would require and the amount of uncertainty linked to it.

- Value: the impact this piece of work would have once completed in helping the teams achieve their goals.

Domain classification system and Project plan

In order to provide clear indicators of what work each document, task, or meeting is related to, we came up with a domain system that identifies each project with a unique combination of names and numbers. This system is divided into the following parts:

- Domain ID: a combination of letters and numbers, unique to each project.

- Domain name: the name of the pillar the piece of work belongs to.

- Domain area: the specific project inside the pillar.

For example, our contributions project was named:

DS-03.02 | Operations | Contributions process

These domains are then used in our Jira objectives and epics, as well as in every document related to that piece of work, giving us a common language to reference and identify each project.

The combination of this domain system and the project map formed our Project Plan, which we built using Google Sheets and connected to all relevant pieces of information. This plan became a very useful tool for phasing the work over time, planning roadmaps, and assigning responsibilities using a RASCI matrix.

All these tools helped us professionalise the team’s practices, enabling us to measure and track the work we produce — an invaluable asset when discussing project resourcing and demonstrating our impact. They also provide the team with certainty, establishing a shared rulebook that supports smooth collaboration and well-documented outcomes.

I made sure to communicate openly and to consider the team’s voices throughout the project, using methods like retrospectives to evaluate our satisfaction with the framework and identify areas for improvement.

One recurring challenge has been the difficulty of keeping systems like Jira up to date while also focusing on producing work. We plan to address this by establishing shared routines and guiding the team through maintaining these tools, with the goal of building confidence and a stronger sense of ownership.

Other design systems work

Planning for a distributed design system

Canonical

Design systems

Translating the Design System’s Vision into Action: A Professional Set of Tools, Rituals, and Practices

In November 2023, after six months of new management, I was entrusted with leading a Working Group dedicated to relaunching our design system. Initially, the group consisted of four designers, each dedicating 20% of their time to modernising our tooling and productising the system under a new mandate.

Since then, the team has grown to include 6 UX designers, 1 content designer, and 4 visual designers. In this case study, I will explain how I organised and led this team, establishing a professional framework to deliver on our vision.

At Canonical, our teams work fully remote and in different countries, but with significant overlap in time zones.

The starting point

During the first six months, I focused on making the best use of the allocated time. I asked our designers to block a full day each week, free from any meetings related to other work. We found that Mondays worked best, as they tended to have fewer meetings and wouldn't disrupt their product work flow. This approach also encouraged higher engagement and fostered a social environment around the work, similar to a hackathon. It made the experience more enjoyable and created an element of accountability.

The initial challenges were mostly structural, so I scheduled working meetings where the team could discuss key decisions like the tiered system, the contributions process, and documentation workflows. As time passed and we refined our strategy, roles became more focused on individual interests and skills, allowing us to accomplish more work simultaneously. However, this also required increased evaluation, steering, and oversight, which led to the need for common rules and practices to scope, track, and review each other’s work.

The team playbook

In conversations with managers and our engineering counterparts, we identified the need for a common source of truth about how our team operates and the standards for collaboration and work. This includes aspects such as work estimation and accurate time tracking, as well as unifying our meeting notes and providing a single document that anyone could reference to understand our goals and shared culture.

This playbook included some key pieces of information:

- General information about the group: a charter outlining the team’s purpose, a list of members and their roles, our recurring meetings, and all relevant links to resources like our Figma folder, code repository, and more.

- Project planning practices: our standards for tracking work in Jira, along with a domain classification framework to give structure to our sub-project names and provide a reliable way to understand the work being discussed at any given time.

- Other sources of truth: beyond team rules, we also needed to document solution specifications for stakeholder approval, which we compiled in a document called Brain; and a dedicated space for documenting work intended for our design system site, which we called “Design Systems Index”.

- Meeting notes: all non-project-specific meeting notes, such as standups and stakeholder updates, were documented in this section.

- A shared sources list: a collection of readings that have shaped our understanding of the project over time.

This document became the foundation of our ways of working and was later adopted and developed further by other working groups within the company.

Understanding the team

Our working group is an area that each team member voluntarily chooses to contribute to, offering an opportunity to work on horizontal initiatives for the design team, alongside their product team responsibilities. Given these circumstances, I aimed to make the work as enjoyable and rewarding as possible, within the boundaries of our vision and stakeholder expectations. I also saw this as a chance for team members to develop skills that would support their career progression — for example, helping a mid-level designer learn to autonomously generate work within an uncertain scope.

With these values in mind, I led a workshop to map the team’s skills, interests, and specific design system expertise, which later helped us allocate resources more intentionally across projects.

Mapping the project

To deepen our knowledge of design systems, we consistently referred to key thought leaders in the field, such as Nathan Curtis and Nate Baldwin from Adobe Spectrum. We also drew lessons from established systems like IBM’s Carbon, the GOV.UK Design System, Adobe Spectrum, GitHub’s Primer, among others.

Based on this understanding, I mapped the project to capture every possible area of work needed to reach a good level of completion for the system. I divided the project into three main sections:

- Framework: this includes all the foundational work where we define our theoretical approach and make decisions on structure, processes, and tools. For example, this covers our approach to Figma libraries and key processes like the Contributions process.

- Toolkit: this section focuses on the main ways our users interact with the system. These are the resources that most designers and engineers will consume, and they represent the practical implementation of the Framework decisions. Examples include our libraries, code repositories, and documentation sites.

- BAU (business as usual): both the Framework and Toolkit categories involve recurring work, from the lifecycle management of different elements, to updates based on new data or insights, or general maintenance. This category groups all of that ongoing work.

Each area of the system is composed of pillars of work, which are the main categories we used to group tasks of a similar nature. These are:

Framework:

- Strategy: the vision and adoption plan.

- System architecture: structural decisions, such as tiers, component levels, library hierarchy, etc.

- Operations: processes like the documentation lifecycle or the contributions process.

Toolkit:

- Foundations: the translation of brand elements into tokens.

- Building blocks: essential elements like components, patterns, and modules that designers and developers use to build UIs.

- Resources: assets like the actual libraries and the documentation websites.

These pillars are made up of our projects, also known in Jira as Objectives, within which we organise all the pieces of work required to complete them, commonly known as Epics.

To further understand the sequencing of work in the project, I mapped all dependencies between different projects, which helped us identify what work was blocked by other tasks.

Finally, to provide a timeline of work to achieve an MVP of the new design system, I led a workshop with all key stakeholders (design management, engineering management, brand designer, and the project leads within the working group) to understand the priorities between different pieces of work. We mapped all projects across two axes:

- Effort: understood as the combination of the time the task would require and the amount of uncertainty linked to it.

- Value: the impact this piece of work would have once completed in helping the teams achieve their goals.

Domain classification system and Project plan

In order to provide clear indicators of what work each document, task, or meeting is related to, we came up with a domain system that identifies each project with a unique combination of names and numbers. This system is divided into the following parts:

- Domain ID: a combination of letters and numbers, unique to each project.

- Domain name: the name of the pillar the piece of work belongs to.

- Domain area: the specific project inside the pillar.

For example, our contributions project was named:

DS-03.02 | Operations | Contributions process

These domains are then used in our Jira objectives and epics, as well as in every document related to that piece of work, giving us a common language to reference and identify each project.

The combination of this domain system and the project map formed our Project Plan, which we built using Google Sheets and connected to all relevant pieces of information. This plan became a very useful tool for phasing the work over time, planning roadmaps, and assigning responsibilities using a RASCI matrix.

All these tools helped us professionalise the team’s practices, enabling us to measure and track the work we produce — an invaluable asset when discussing project resourcing and demonstrating our impact. They also provide the team with certainty, establishing a shared rulebook that supports smooth collaboration and well-documented outcomes.

I made sure to communicate openly and to consider the team’s voices throughout the project, using methods like retrospectives to evaluate our satisfaction with the framework and identify areas for improvement.

One recurring challenge has been the difficulty of keeping systems like Jira up to date while also focusing on producing work. We plan to address this by establishing shared routines and guiding the team through maintaining these tools, with the goal of building confidence and a stronger sense of ownership.

Other design systems work